If almost all verse is tough to translate, language poetry presents a challenge all of its own. Mario Martín Gijón, who was born in 1979 in South-West Spain and holds an academic position at the University of Extremadura, has published four collections of poetry in which he uses all the typographical tools at his disposal—including hyphens, slashes, spaces, line breaks, and parentheses—to stretch the morphology of Spanish into untrodden semantic territory.

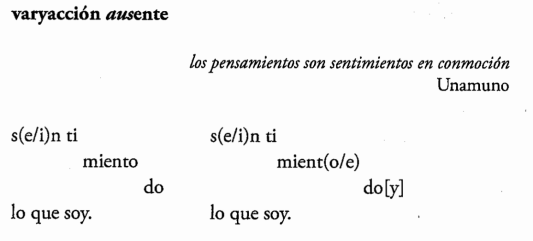

Here, for example, is a poem from his 2013 collection Rendicción (whose title activates the concept of diction in the noun rendition):

Within a minimal space, the poet maximizes semantic potential: the two verses, placed in parallel columns, evoke a range of morphologically related concepts: sin ti (without you), sentimiento (feeling), miento (I am lying), miente (it lies) todo (everything), doy (I give), so that one verse can read, in one of its many guises: “feeling [is] all I am,” and the other, mirroring it, “without you everything I am lies,” “without you, I lie, I give what I am,” or “feeling, I give what I am,” and so forth.

The poet and translator Terence Dooley has taken on the challenge to render Martín Gijón’s collection into English—although, as his witty translation of the collection’s title indicates, he’s fully aware of the extent to which that task involved a good amount of sacrifice if not capitulation: Sur(rendering).

Surrendering, giving in, letting go: if Martín Gijón’s poems stage, at the formal level, the poet’s handing over control to language itself, letting etymology and morphology steer his associations, their thematic content also underscores the role of rendition as an act and attitude of romantic love. Dooley, in turn, manages to strike a fine balance between the translator’s obsessive pursuit of the original’s meaning in the target language, on the one hand and, on the other, the acceptance of the original’s ultimate elusiveness—much like, in these poems, love never equals possession and the poet is fully aware that the language he uses will never be fully his, even as he takes it apart and puts it back together.

As is to be expected, Loomey is more successful in some instances than in others. For the poem I cited earlier, for example, he found an admirably elegant solution:

Elsewhere, preserving the original’s effect requires considerably more jerry-rigging from the translator. Consider the poem “sueño estival” (summer dream), which evokes the fantasies sparked by romantic absence and the incredulity brought on by an unexpected summer visit:

The Spanish awakens the notion of denial in the adjective “veraniega,” and plays with the words “ve” (sees), “veraz” (truthful) and “a ras de tierra” (at ground level), as well as the hint of an echo between “soñada” (dreamt) and “saña” (fury). Although the translation loses some of the simplicity of the original, it manages to convey almost all its polysemic playfulness.

In other cases, the translator has made somewhat more debatable choices. In the first poem of the collection, for example, an asyndetic parenthetical verse, “(es un sueño no es real despertaré)” becomes “(it is a dream it isn’t real you woke)”, with what seems like an unnecessary, and unjustified, switch from the first-person future to the second-person past tense.

“Translating Mario Martín Gijón,” Dooley writes in the preface, “involves being faithful to his meanings while completely displacing and reconstructing his effects. Words must be found in English (often elsewhere in the poem) capable of the dislocations and relocations, the Russian doll/Rubik cube effect, his method demands. The strange harmony and beauty of his lyric voice must also be reproduced.” The face-to-face edition, as always, invites every reader to become an instant translation critic, scrutinizing every decision made. If that reader is honest enough to acknowledge the enormity of the task, she can only conclude that Dooley has done right by Martín Gijón.

Martín Gijón, Mario. Sur(rendering). Translated by Terence Dooley. Shearsman Books, 2020.

Sebastiaan Faber, Professor of Hispanic Studies at Oberlin College, regularly writes for the Spanish and U.S. media, including CTXT: Contexto y Acción, La Marea, FronteraD, The Nation, Foreign Affairs, Conversación sobre la Historia, and Public Books. His most recent books are Memory Battles of the Spanish Civil War: History, Fiction, Photography and Exhuming Franco: Spain’s Second Transition, both published by Vanderbilt University Press. Born and raised in the Netherlands, he has been at Oberlin since 1999. More at sebastiaanfaber.com.