Verbal Mycology: Olya Stoyanova’s “Happiness Street,” Translated from Bulgarian by Katerina Stoykova

In Bulgarian poet Olya Stoyanova’s award winning 2013 poetry collection “Happiness Street,” translated by Katerina Stoykova and published in 2025, empathy is not merely a byproduct of the reading experience; rather, it is something that permeates and motivates each of her poems.

Throughout “Poemi Conviviali,” music surfaces again and again, sometimes eerie and disquieting, often located in the limbo between life and death, or dream and reality; sometimes as the Dionysian, ecstatic sound of drums and double flutes, but most often as melodies performed on a stringed instrument, the lyre, which is the ancestor of the modern harp.

The work of French poet Gabrielle Althen (pseudonym of Colette Astier) is a simmering broth of intensity, strangeness and wild overgrowth verging on surrealism. These qualities are paradoxically nurtured rather than inhibited by her preference for miniscule, aphoristic snippets of text ‘sculpted’ (her phrase) out of the blank space that envelops them.

James Shea has risen to this age-long challenge in his beautifully crafted translation of “Applause for a Cloud,” Kamakura Sayumi’s latest collection (Black Ocean, 2025). A poet in his own right, Shea brings a crystalline language to the dense and endlessly changeable process of translation, offering English-language readers a ride along Kamakura’s intercontinental itinerary, including stops in Morocco and Italy.

Poignant, and at times breathtakingly honest, “In Farthest Seas” joins a select group of narratives that help us cope with the death of a loved one through the eyes of the writer, who cannot help but transform that pain into a story so that the writer, as well as the reader, may begin to comprehend it.

Miriam Karpilove (1888-1956) wrote at the beginning of the twentieth century, a time when Yiddish women authors were gaining entrance to the world of Yiddish prose, a form from which they had been largely absent. Karpilove’s epistolary novel “Judith: A Tale of Love and Woe” (1911) was composed during a vibrant moment of this minority language’s literary history, when Yiddish literature was carving a new path as a modern world literature after the death of the “classic” Yiddish writers.

This dialogue originated from my reading in August 2024 of Franca Mancinelli’s The Butterfly Cemetery, translated by John Taylor. Every day I put Franca’s collection of essays and narratives in my backpack and set off on long hikes in the high mountains.

Rather than retelling myths, in “The Leucothea Dialogues” Cesare Pavese uses them as a framework for meditations on fate, death, suffering, and the fraught relationship between gods and humans.

Very few historical fiction writers would think to take up the tale of a ninth-century disinherited crown prince on religious pilgrimage as he approaches the end of his life. Yet this is, at least on the surface, the subject Tatsuhiko Shibusawa (1928-1987) engages with in “Takaoka’s Travels,” translated by David Boyd.

How do you write about the compelling need to write, to translate reality into narrative, while also writing about someone who decided not to write? The title of Anne Milano Appel’s English translation, published by New Vessel Press, suitably spells it out: this is “A Fictional Inquiry,” an investigation into the nature of fiction itself and its entanglements with reality.

What impresses me, then, about Katsuhiko Otsuji’s “I Guess All We Have is Freedom”—translated into deliciously playful and decadent English by Matt Fargo—is the way Otsuji’s odd turns and tangents feel at once like true stream of consciousness and yet circle back in again and again upon themselves, all in the name of demonstrating how unstable our sense of reality really is.

At the start of her second memoir, “Parisian Days,” Banine, a French author of Azerbaijani descent, arrives in the promised land. The year is 1921. Paris has newly entered the Roaring Twenties, a time of short respite between the two Great Wars. Banine is only nineteen, and she has just miraculously escaped her detested husband, the distant city of Istanbul where she left him behind, her homeland Azerbaijan and, perhaps most significantly, the grips of the Soviet Union.

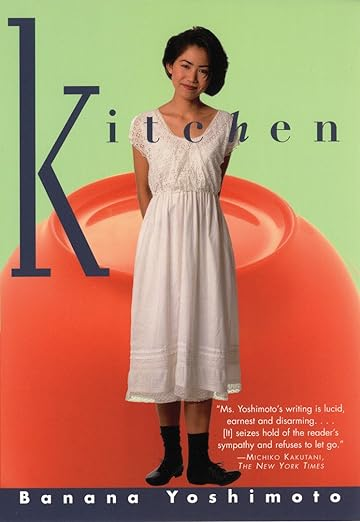

For six years, I have had a tradition: right around the beginning of December, when the Florida heat finally cools off, I slip my copy of Banana Yoshimoto’s “Kitchen” off the shelf and allow it to rekindle a warmth within my being. Translated in English by Megan Backus, the light, intricate, and mouth-watering prose of the novella has delighted me endlessly.